What is living data? That question seemed fitting to explore while nestled high in the Andes Mountains in a city rich with culture that deeply connects its people to the extensive biodiversity that surrounds them.

In the last days of October 2025, I anticipated the wonderful opportunity to present my Master’s research at the Living Data conference – a joint event led by the Biodiversity Information Standards, Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), Ocean Biodiversity Information System, and Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network. The conference provided an occasion for approximately 1,000 people from over 60 countries to share their unique stories and data challenges during the many concurrent sessions held at the Grand Hyatt in Bogotá. A common objective brought attendees and presenters alike together to transform and inform how we collect, share, and use biodiversity information in ways that truly respect and reflect local realities. As someone invested in the stories that data tell and the stories they do not, I was curious to learn from those who work to create the systems that collate and organize data, from those who determine how data are defined, from those with embodied knowledge who translate information into data, and from many more whose daily lives and work are directed by the resulting interpretable, and accessible data.

With my curiosity rising and my PowerPoint presentation in hand, I made my way through the busy venue. The crowd and anticipation may have created a slightly nervous atmosphere, but I found calm in the smell of fresh rain and coffee, and in the energy of attendees eager to learn and share knowledge.

Presenting with Local Contexts

I was fortunate to receive support from Early Career Ocean Professionals and the Students on Ice Foundation to deliver my presentation as part of Local Contexts’ workshop, “Understanding Indigenous Data Provenance, the CARE Principles, and Local Contexts.” During the workshop, I shared insights from my study that explored the suitability of six decision-support tools–including a marine atlas, participatory mapping, ArcGIS StoryMap, and virtual reality–to collect and communicate place-based knowledge in a spatial planning context. My research examined how these tools can support knowledge representation throughout a planning process by highlighting the design and use limitations and identifying the characteristics and planning stages for impactful use. The workshop’s focus on Indigenous data sovereignty and innovative tools such as Labels and Notices provided a powerful forum to discuss ethical data governance and to share global case studies, directly aligned with the conference’s objectives to connect policy and science, foster interoperability, and expand access to the knowledge needed to monitor progress toward planetary conservation. This experience reinforced the importance of incorporating local contexts and knowledge systems to inform decision-making in changing environments, ensuring the tools and standards we adopt reflect, respect, and empower the communities they are meant to serve.

Recurring Thoughts among Various Topics

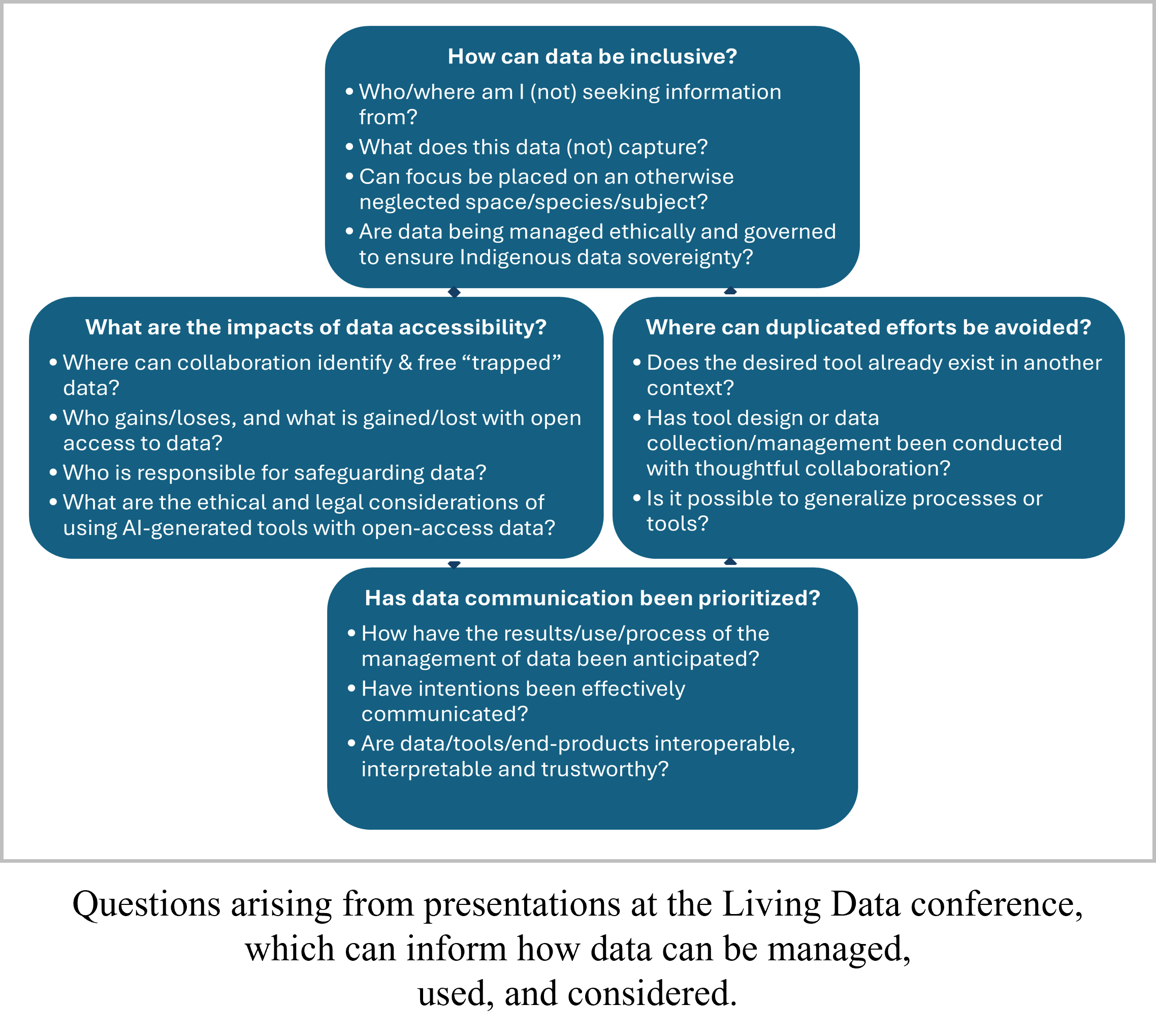

Throughout the conference, I attended sessions on topics ranging from global data infrastructure and DNA-derived biodiversity data to overcoming barriers in data sharing and strengthening community engagement. Among these topics was an interconnected web of questions and concepts that identified shared priorities and the need for thoughtful approaches to data. Summarized in the figure below and described in the following paragraphs, these questions can inform practitioners, software engineers, researchers, citizens, and avid learners in all fields on how to use, collect, communicate, and think about data.

How to be Inclusive in Data?

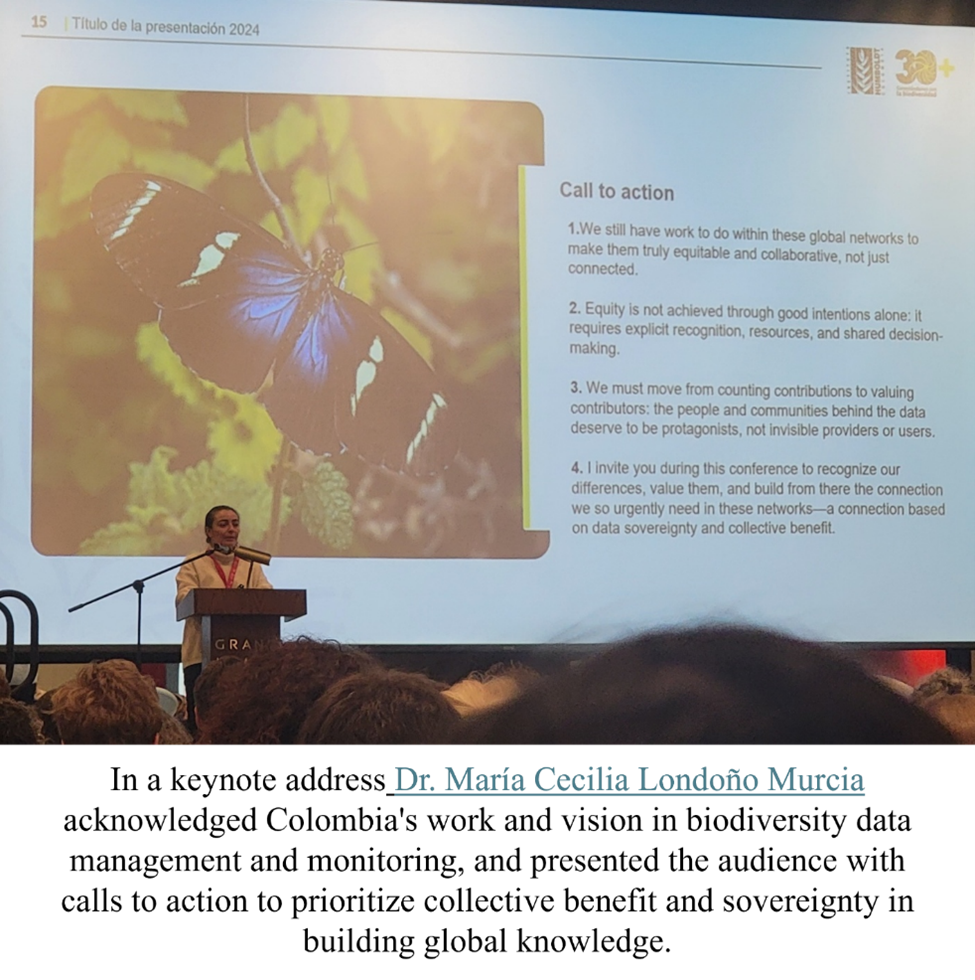

Numerous questions arose about the inclusivity of data. I heard many conversations about centring on the “Global South”; however, these discussions occurred without acknowledging the complex realities of the people, landscapes, and geographies that have been placed on the periphery, or, frankly, out of mind. Some presentations seemingly relied on this simplistic geographic label to address the current exclusive nature of data by stating that projects will be “expanded into the global south,” but this claim masks systemic inequities. Asking how to genuinely refocus attention, incentives, funding, and resources toward otherwise neglected groups, species, and spaces can set a path toward inclusivity in data. Understanding the histories and data provenance—the stories behind how data are collected, who they represent, and the contexts that shape data—also enables inclusivity through accountability, transparency, and trust in the data’s origins and use. As Dr. Maui Hudson, Kaite Lee Riddle, and speakers from the “Experiences & Lessons of Managing Community-based Biodiversity Data in Ethnic & Local Communities” and the “Trust, Traceability & Transparency” sessions pointed out, understanding data provenance is necessary in the governance of Indigenous data and for the support of data sovereignty.

Where Can Duplicated Efforts Be Avoided?

With inclusivity, accountability, and trust comes collaboration. The importance of thoughtful collaboration was highlighted in a story told by a speaker at the “Scaling AI For and Across Biodiversity: Data Collection and Curation in AI-Driven Biodiversity Research” symposium. The speaker noted the surprise of a developer who spent five years designing a tool before discovering that a similar tool already existed. Through meaningful and thoughtful collaboration, redundancies and potential duplication of effort can be identified and avoided. But it is essential to acknowledge that data are as complex as the components that comprise them, and that nuances of data may not be captured by a generalized tool.

Has Data Communication Been Prioritized?

Data communication is not merely a technical task but the means by which impactful biodiversity science can prompt changes through policy. The sessions left me wondering whether the communication of data and data tools—their intentions, anticipated results, and management processes—have truly been prioritized from the sources to the end products. Speakers from the Long Live Biodiversity Data: Knowledge Transfer and Continuity across Research Projects symposium emphasized the need for tools and datasets to be interoperable and interpretable, and the outcomes of use to be anticipated before sharing data. Careful communication highlights that designers, managers, and scientists value the data and those who use the data and thereby improves data usability and informs decisions as intended.

What are the Impacts of Data Accessibility?

Another critical set of questions revolved around data accessibility: When should data be accessible, and who is impacted by access? Several speakers stressed that while a notable lack of fine-resolution data remains in specific geographic contexts—such as areas distant from functioning roads—a more pressing challenge is often not the absence of data but limited access to and awareness of existing datasets. Maheva Bagard Laursen, Programme Officer at Global Biodiversity and Information Facility, Denmark, emphasized that this issue stems largely from capacity constraints rather than an unwillingness to share data. Freeing “trapped” data by publishing and mobilizing biodiversity information currently locked away—whether in physical archives, paywalled publications, or inaccessible institutional databases—emerged as a priority topic at Living Data 2025. Data accessibility decisions must consider both the benefits and the risks of data sharing. How can one ensure that data are used as intended, especially in open-access contexts where broad sharing can increase the risk of misinterpretation or misuse? Vanessa Pitusi from the Arctic University Museum of Norway offered a powerful example: maintaining knowledge sourced from Indigenous or local communities in the language in which it was initially shared helps to preserve its contextual meaning. Beyond human knowledge, she emphasized that embodied knowledge extends to species themselves—such as insects carrying unique biochemical and genetic markers representative of their environments—highlighting that data are deeply tied to the ecological and cultural contexts of their origin.

So, what is Living Data?

Data aren’t simply points or value entries; they are a series of efforts pursued by collectors and sourced from species and spaces. And, not to be overly anthropomorphic, I understand data to reflect the dynamics of their sources. Data change through and over time and require consistent long-term attention. Some choose to amplify data while others have discredited, ignored, silenced and even entrapped data. Data embody stories, which they can reveal. As such, living data holds contextual richness and requires respect and integrity in its use in order to maintain meaning and relevance as data moves through knowledge systems, software, and policies.

Author: Jumanah Khan

Jumanah Khan is a knowledge mobilizer and conservationist who holds a Master of Marine Management degree from Dalhousie University, where she explored how place-based knowledge can inform coastal spatial planning in Nova Scotia. She conducts research with the Ocean Frontier Institute’s Benthic Ecosystem Mapping & Engagement (BEcoME) project as a Research Associate at Dalhousie University, contributing to studies on the role of social engagement and community knowledge in understanding benthic environments.

Credits: Except for the photograph of J. Khan presenting her paper, all other photographs are by Jumanah Khan.

Tags: Information Use & Influence; News; Science-Policy Interface; Scientific Communication