The current crisis unfolding in eastern Europe on Ukrainian soil has brought renewed media attention to the international geo-political stage of the importance of energy infrastructure. How energy is produced, processed, transported, and ultimately consumed plays a dominant role in shaping our world. So does the choice of that energy source. In the context of a world seeking a de-carbonisation transition, in order to respond to the challenges of climate change, hydrocarbon-based energy infrastructure projects, such as new pipelines, are at the centre of a swirl of controversies with many dimensions. Since hydrocarbons will continue to be burned for decades during this transition, should we continue to build new infrastructure capacity such as pipelines? How should the impacts of such decisions, for or against, be assessed?

Such decisions require the complex activities of information gathering, processing, interpreting and decision responses that make up the sub-field of environmental management called environmental impact assessment, or as the term is now increasingly called, simply impact assessment (IA for short). In one sense, the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and its various reports constitute an ongoing global project of IA, though formally the International Association for Impact Assessment, the international body overseeing this field, is not involved in IPCC’s work as IAs tend to be restricted to assessing projects on a smaller scale. Canada’s federal agency responsible for IA, the Impact Assessment Agency Canada (IAAC) (called the Canada Environmental Assessment Agency prior to August 2019), has authority on federal lands (and in certain trans-provincial cases) to oversee this crucial aspect of management of proposed projects such as energy infrastructure.

The name change reflects the growing understanding of the diverse (i.e., not just environmental) nature of the impacts of such projects, especially their coupled socio-ecological character. People and place, whether at the very local level or the world stage, are jointly and reciprocally impacted in feed-back loops that we can no longer ignore. The name change also reflects a central insight well known to EIUI researchers: that “information” relevant to assessing impacts in the field of environmental management increasingly comes from a wide plurality of academic disciplines (i.e., beyond just biophysical ones), and also from non-academic sources, ranging from Indigenous and non-Indegenous knowledge of local place, to national citizen-based environmental organizations, to specialized knowledge emerging from international bodies of peer-reviewed science such as the work of the IPCC.

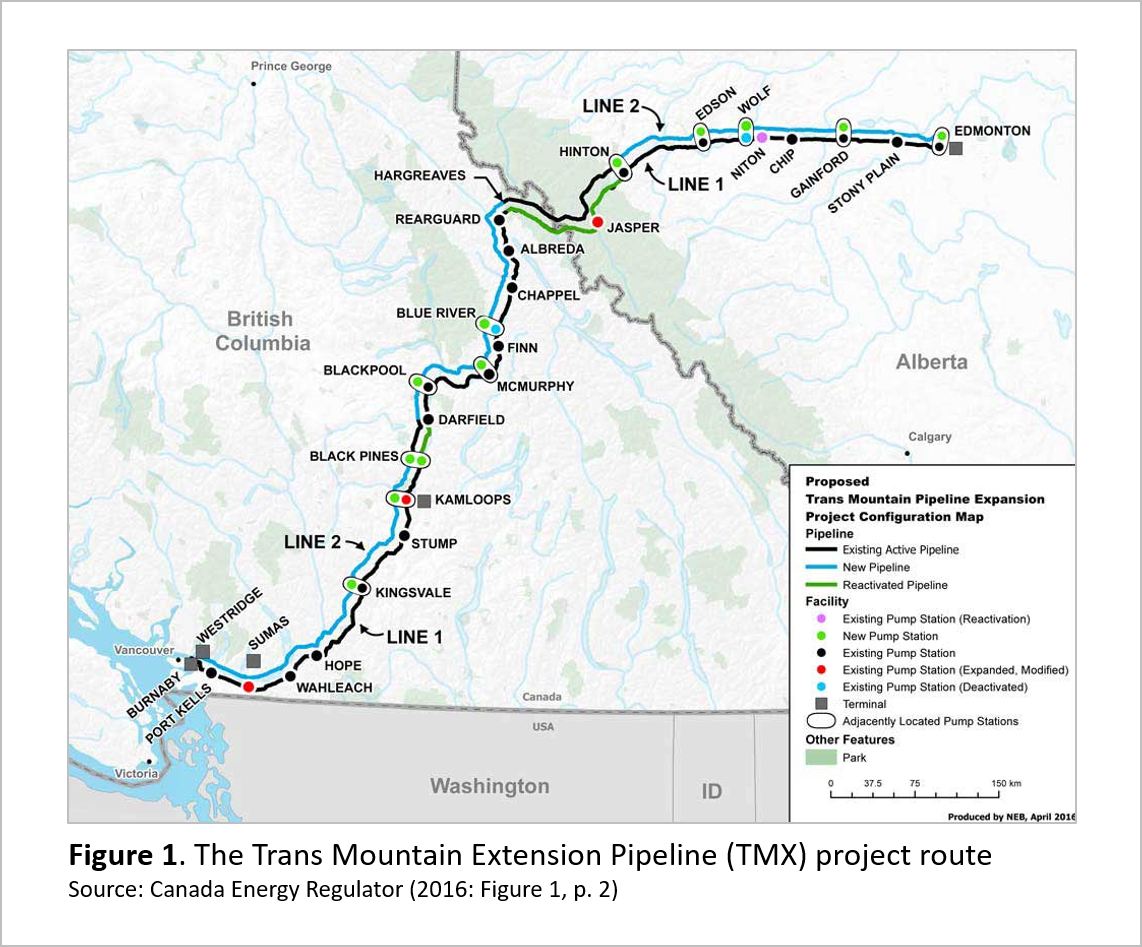

A recent paper I co-authored with Moira Harding explores the IA process at the heart of one of Canada’s more controversial energy infrastructure projects: the Trans Mountain Expansion Pipeline (TMX) project, extending from outside Edmonton, Alberta, to Burnaby, British Columbia, in the Burrard Inlet near Vancouver. My own work on IA, which includes NEDIA, a SSHRC-funded project, grew out of my collaborations with EIUI co-founder Peter Wells, a long time contributer to the field in Canada.

“One Pipeline and Two Impact Assessments: Coproduction, Legal Pluralism, and the Trans Mountain Expansion Project,” as the title suggests, draws from two disparate fields, Science and Technology Studies (STS) and Legal Studies, reflecting the respective areas of expertise of the two authors. This paper tells the double story that has unfolded over nearly a decade, at the centre of which are two impact assessments—one overseen by then-called National Energy Board (NEB) (known as the Canada Energy Regulator since August 2019)—and one undertaken by the Tseil-Waututh Nation(TWN), whose ancestral lands include the shores of the Burrard Inlet.

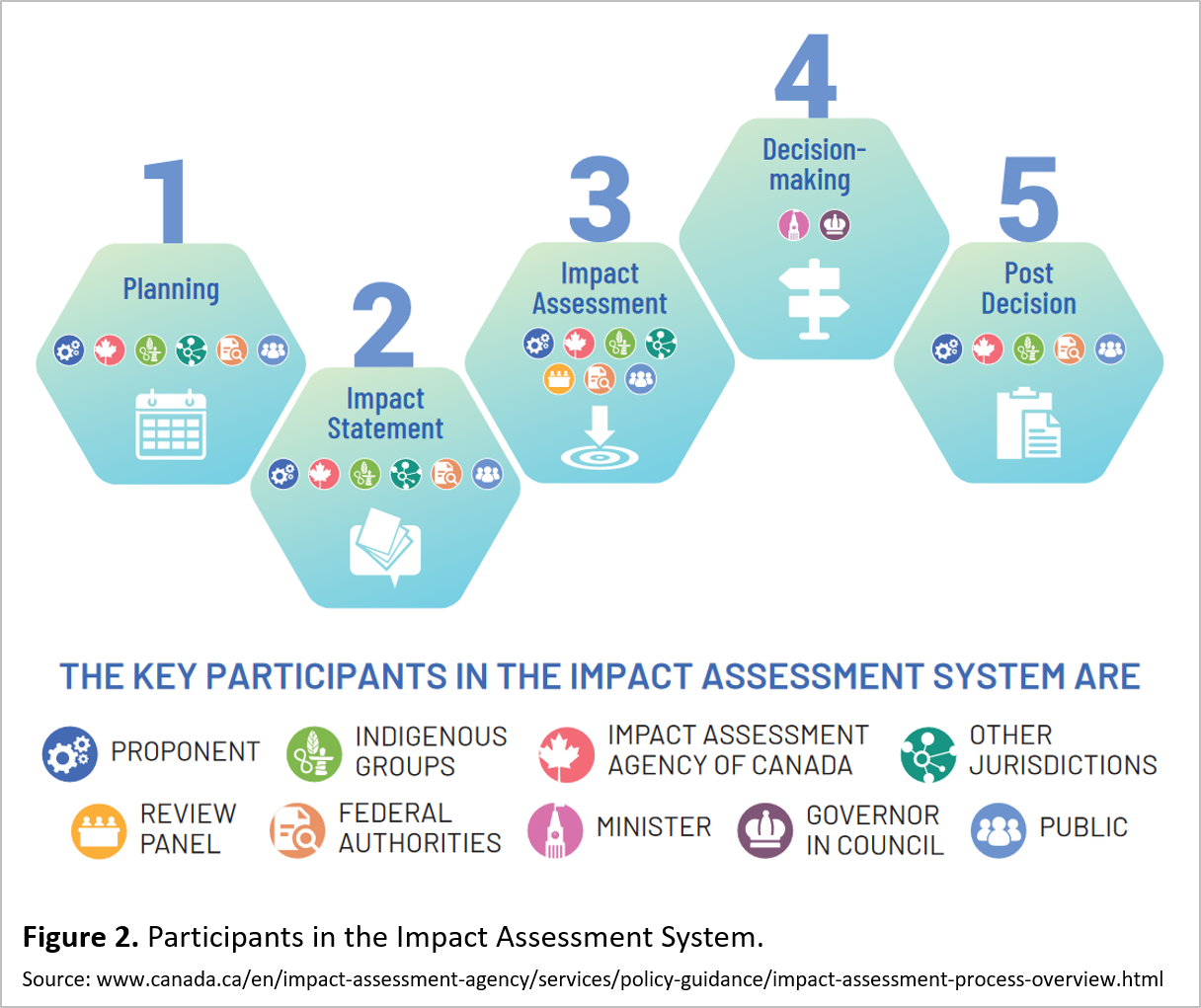

IA is at heart a kind of knowledge contest, where claims about the impacts of a project, in this case the expanded pipeline, are debated by those involved, either in person, in writing, or both. From an information management perspective, it is important to know that the basic structure of IA information debate. After initial scoping, a key stage involves the formal claims made by the proponent in their “Impact Statement” (in this case, by the US-based energy company Kinder Morgan) (see Figure 2). The next stage involves formal opportunites for responses by intervenors and other participants (including government departments) to that Impact Statement, with the National Energy Board in effect playing the role of adjudicator. Decision stages by the government follow, with conditions informed by the assessment process serving to guide both the project’s completion and ongoing monitoring and follow up to ensure impacts remain as predicted, which in part serves to test the quality of the information process itself. A simplified graphic (see Figure 2, produced by IAAC) captures the basic structure of the process followed in the IA for this pipeline.

The TMX project, now nearing the final stages of construction, in part retraces the old pipeline, and in part introduces new routes, but the goal is to expand export volumes leaving from Burnaby by up to seven-fold, including increasing the number of large tankers leaving this port. For the initial proponent, the story of the IA related to this project began back in 2012 with community engagement; for TWN the story long predates that period, grounded in their lived experience of the Burrard Inlet going back centuries.

The paper’s main goal was to do some basic descriptive and comparative work of two quite distinct IAs by Canada and by TWN, respectively, in relation to this project. Our methods involved document analysis using only publically available sources, with some perspective added by informal fact-checking interviews with persons involved, and drawing on extensive literature on IA for context. Despite this straightforward methodology, this analysis was no easy task for several reasons. On Canada’s side, the process of IA stretched out over several years (and over the full length of the pipeline), and involved two distinct iterations (due to legal challenges at the level of the Federal Court of Appeal launched by TWN and others). Ultimately many thousands of pages of documents record evidence of information gathering and reporting based on the involvement of provincial and federal departments, Indigengous nations, communities, non-governmental organizations, private-sector groups, totalling over 1600 individuals. This number does not include the mountains of documents associated with the various legal challenges around this project. Fortunately for the authors, the NEB was responsible for providing a final exhaustive, consolidated report of the process involved, comprising several chapters within a nearly 700-page report, which formed the basis of our analysis of Canada’s IA, along with supporting documents to situate this IA within the broader scholarship on IA.

Equally challenging was our effort to describe the work of TWN, in the context of the TMX process, of providing what was one of the earliest entirely Indigenous-led IAs for any project of this size or scope. This TWN assessment was completed in 2015, as part of its Assessment of the Trans Mountain Pipeline and Tanker Expansion Proposal, which it submitted also as evidence to the review panel process conducted by the NEB (effectively part of stage 3 in Figure 2). Along with other strategic TWN documents recording their decades long, and ongoing collaborative work with academic and government scientists on the Burrard Inlet as a socio-ecological system, the TWN Assessment constitues a complex weaving together of TWN traditional teachings, community consultation, anthropological and archeological evidence, along with reports by five consultants. The latter reports focussed on aspects of risk calculation, ecological and human health impacts, and projections of scenarios of response and recovery should a tanker spill of oil occurr in the Inlet. It was the projections that mirrored most closely the general scientific modelling methods followed in the NEB-supervised IA process. TWN did not consent to the TMX, and their opposition to it continues to this day, judging that it “continues to infringe upon the rights, title and interest of Tsleil-Waututh Nation.”

Alone, this work of describing and juxataposing two very different IAs was important, and the first of its kind for this famous project in Canada. Within the evoloving landscape of IA scholarship in Canada and around the world, the role of Indigenous peoples’ rights and responsibilities in assessing impacts of projects of this type is taking centre stage, not least in light of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), to which Canada is a signatory and pursuant to which it has enacted legislation in June 2021. In Canada Indigenous-led IAs are still an evolving possibility, and are beginning to attract the attention of scholarship in this field (Sankey, 2021). We contend that the complex contours of information management will play a central role going forward in Canada’s efforts at reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Further, our paper dug into the complex relationship between law and science, as it related to how two central concepts to the science of IA are interpreted and implemented in the information management that is central to IA: “signficance” and “mitigation.” Significance is a key analytical term for IA, for it determines and directs the information gathering, interpretation, and decision making stages of IA. If a project’s negative effects are “significant,” this determines much regarding whether and how a project goes forward. Likewise “mitigation,” or our capacity to lessen negative effects, not only qualifies whether and how a project goes forward, but also directs to a large extent how follow up measures are implemented. Our paper shows how these terms meant something different for Canada and for TWN in the context of the IAs in question, in part because of differening social and legal realities of the respective governments. Bringing to light these differences helps to show how complex processes of information management such as are central to IA are dependent on, and help “co-produce,” broader legal contexts. The degree to which science fields (social, human, biophysical) and their organizing concepts are embedded within larger political and legal contexts is a central insight of the field of Science and Technology Studies. The term “co-production” in the title of the paper was coined by STS scholar Sheila Jasanoff (Harvard University) some years ago to capture exactly this insight. But its use in information management circles tends to mean something different now, namely, the hopefully collaborative possibilities of multi-sourced information (Turnhout et al., 2020). Our paper argues that “information” as such requires more nuanced attention than merely the plurality of its sources. In our drive to honour “data” gathering as the ultimate gift of computerized power and efficient technologies of surveillance, we must not lose sight of what matters most: what information means to those who live with its consequences. Such meaning is always embedded in ways of life that our legal systems help to codify and enforce. These systems can either open up or close down possibilities for information to empower our collective efforts to live well with one another and our planet. Closing down such possibilites is the essence of totalitarianism. Just ask Russians.

References

Stewart, I. G., & Harding, M. E. (2021). One pipeline and two impact assessments: Coproduction, legal pluralism, and the Trans Mountain expansion project. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 016224392110573. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211057309

Abstract: Canada’s Trans Mountain Expansion Pipeline project is one of the country’s most controversial in recent history. At the heart of the controversy lie questions about how to conduct impact assessments (IAs) of oil spills in marine and coastal ecosystems. This paper offers an analysis of two such IAs: one carried out by Canada through its National Energy Board and the other by Tsleil-Waututh Nation, whose unceded ancestral territory encompasses the last twenty-eight kilometers of the project’s terminus in the Burrard Inlet, British Columbia. The comparison is informed by a science and technology studies approach to coproduction, displaying the close relationship between IA law and applied scientific practice on both sides of the dispute. By attending to differing perspectives on concepts central to IA such as significance and mitigation, this case study illustrates how coproduction supports legal pluralism’s attention to diverse forms of world making inherent in IA. We close by reflecting on how such attention is relevant to Canada’s ongoing commitments, including those under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Sankey, J. M. (2021). Using Indigenous legal processes to strengthen Indigenous jurisdiction: Squamish Nation land use planning and the Squamish Nation assessment of the Woodfibre liquefied natural gas projects. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of British Columbia. https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0402462

Turnhout, E., Metze, T., Wyborn, C., Klenk, N., & Louder, E. (2020). The politics of co-production: Participation, power and transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42, 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009

Author: Ian G. Stewart