My first glimpse of the Mediterranean was caught from the tram window as I arrived in the Old Port of Nice. A graduate of Dalhousie University’s Master of Marine Management program, I was on my way to present my master’s research at the One Ocean Science Congress (OOSC)—an event that felt dynamic and expansive like the sea surrounding the meeting venue.

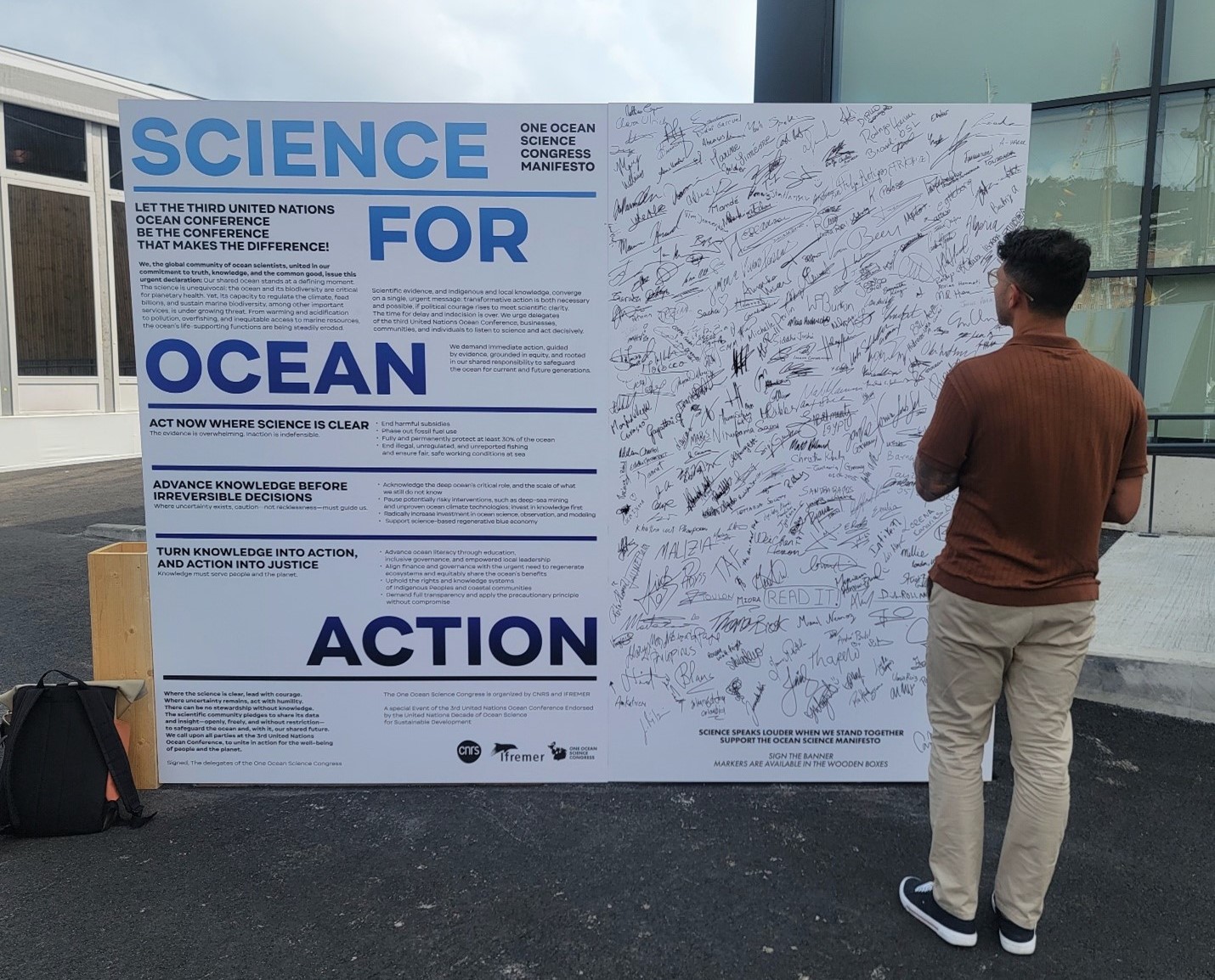

The OOSC was a global convergence of ocean scientists, policymakers, Indigenous leaders, and those sharing organizational resources, all united through a sense of urgency and hope. The Congress aimed to mobilize scientific knowledge to inform global ocean conservation and sustainability decision-making. Collaborative findings from the event also served as a foundation for the Third United Nations Ocean Conference.

The OOSC was a global convergence of ocean scientists, policymakers, Indigenous leaders, and those sharing organizational resources, all united through a sense of urgency and hope. The Congress aimed to mobilize scientific knowledge to inform global ocean conservation and sustainability decision-making. Collaborative findings from the event also served as a foundation for the Third United Nations Ocean Conference.

Dr. Lisa Levin, a renowned marine ecologist, reminded us in her keynote: “We need to move from knowing to understanding, and from understanding to action—because there are no other options but to act with knowledge-based actions. We have one world, one ocean—we are the ocean.”

Concurrent sessions and plenaries reflected this sentiment by discussing and gathering attendees’ insights on topics ranging from successes found in applying Indigenous and local knowledge systems to rapidly evolving contemporary concerns, the limiting nature of current ocean governance approaches, and advances in marine genomics and climate resilient communities. What stood out most was the chorus of voices echoing the same truth: modern human impact on the ocean has been overwhelmingly negative, but the tide can turn through collective, informed action.

Interconnected Themes, Fragmented Systems

Each day at the Congress unfolded with highs of inspiration, lows of sobering reality, and a constant current of connection. The themes—resilience, biodiversity, technology, equity, governance—were continually interconnected. Yet, as many speakers noted, our governance, management, and science approaches remain divided by siloed systems and tainted politics.

Dr. Teriitutea Quesnot, a panelist of the “Strengthening the Link Between Science and Policy” session, reflected on the concept of the Congress and “one ocean.” Dr. Quesnot shared that geographically, it can be seen that the oceans are connected, much like those that rely on the body of water. Politics, however, introduces rigid borders and didactic boundaries that hinder collective action.

This observation made me think about the words of another panelist: “Sustainability is not enough. We need to be nature positive.” But, what does it mean to be nature-positive? After this and other sessions, I understood this term as a call for intentional transformation…a transformation to heal the ocean and our relationships to it. To do this, we must think beyond our disciplines, our imposed and sometimes undefined jurisdictions, and build trust and partnerships to prompt proactive stewardship. Numerous presentations discussed finding connections in fragmented systems via decolonizing of funding streams, rethinking which activities received support, and finding new ways of taking action in current contexts, not simply filling gaps and applying band-aid solutions.

During one discussion, an attendee said: “Community action and knowledge require the backing of institutions to improve trust, necessitating a restructuring of economic, engagement, and investment models.” The attendees continued to consider the need to acknowledge and address the mistrust in the institutions and entities that the public perceives as responsible for addressing ocean challenges. This mistrust lies in the inability of community members to feel they are heard, and to see themselves in policy development and decision-making.

From Data to Decisions: Bridging Science and Policy

One of the most compelling themes at the Congress was the persistent gap between scientific knowledge and real-world action. One speaker observed: “The contexts of collective effort have to change. The whole system must be understood as the basis for policy and action. The distance between science and action needs to be reduced. And now science has a role in politics—at a time when policy may not even influence politics.” This sentiment set the tone for discussions on ensuring that research and evidence directly inform decision-making processes.

The Congress highlighted the importance of robust statistics and unified data systems to inform regulation and legal decisions while safeguarding data security and sovereignty. For example, judges in Ecuador and Panama are increasingly relying on scientific evidence to uphold the ocean’s rights. As Dr. Maria José de la Fuente discussed Panama’s pioneering legislation and recent court decisions, she stated: “We are seeing a new era where the ocean is not just a resource, but a subject of rights—this is changing how judges rule on marine protection and fisheries.” This development represents a shift from viewing the ocean as property to recognizing it as a living entity with rights. This shift is influencing language—as I had observed speakers moving away from using the “ecosystem services,” which implies human-centric biases to terms like “ecosystem functions.” Also influenced by this shift in recognition that the ocean is alive are legal and regulatory frameworks informed by diverse datasets.

Data, Genomics, and Collaboration

A session on marine genomics brought the global picture into focus. Using the Red Sea as a model for understanding climate change impacts on marine genomics, scientists called for coordinated, global efforts in genomic data collection. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s data center maps revealed significant gaps, especially in the Global South, underscoring the need for equity in scientific research and resource allocation. “Unified data and reduced double investment in projects can give opportunity to more compatible efforts,” one presenter noted, emphasizing the value of collaboration over competition.

Adaptive Management and Temporal Thinking

Storytelling played a prominent role in conversations about adaptive management at the Congress, serving as a bridge between tradition and innovation. Speakers brought to life the enduring wisdom embedded in practices like the Polynesian “Rahui” and Mexico’s zonas de refugio—temporary closures designed through adaptive, co-management strategies. These stories illustrated how embracing uncertainty can be a productive force in conservation, rather than a barrier.

The “Rahui,” for instance, is a customary practice where communities temporarily restrict access to certain marine or terrestrial areas to allow resources to recover. Similarly, Mexico’s “zonas de refugio” are designated zones where fishing is temporarily halted, often in response to ecological signals or community needs. Both approaches are rooted in the understanding that ecosystems are dynamic and that management must be flexible enough to respond to change. “Bringing time into conversations about spatial management is essential,” a panelist explained. “With temporary closures, permanency doesn’t have traction—as seen in precolonial management.” This perspective challenges the conventional conservation paradigm that often prioritizes permanent protected areas. Instead, it recognizes the value of cyclical, adaptive measures that can be tailored to social, cultural, and ecological realities.

Several speakers challenged the audience to reconsider some people’s comfort with the idea of permanence. “Nothing is permanent,” one panelist stated while pointing out that even laws and protected areas—seen by some as fixed—are frequently subjected to change. Temporary closures can force adaptive management, requiring ongoing monitoring, community involvement, and willingness to adjust strategies as conditions evolve. This approach also honors the plurality of time—acknowledging that ecological processes, cultural practices, and management needs operate on different timelines.

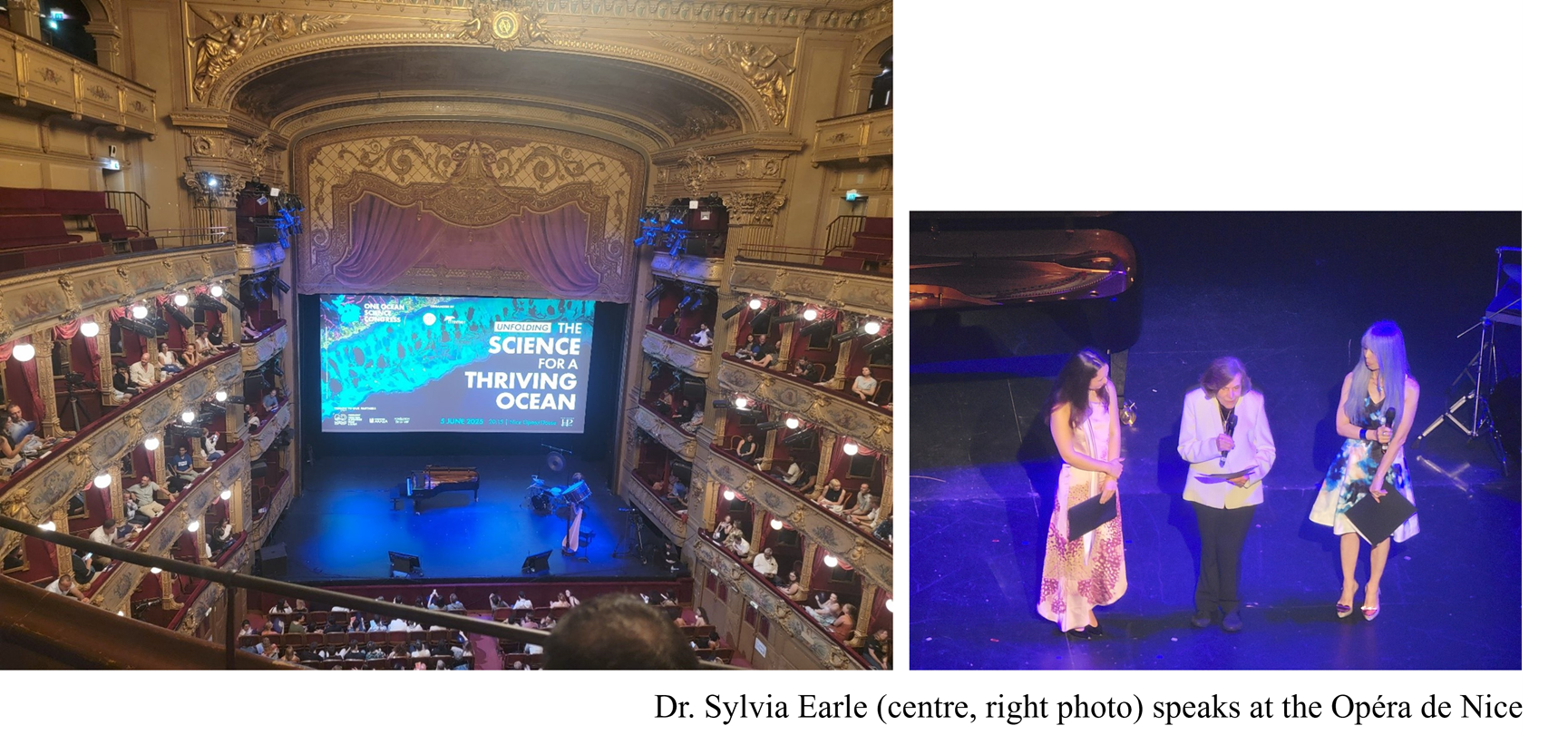

A Night at the Nice Opera: Science Meets Art

One evening, the Congress led us to the Opéra de Nice for La Mer: A Tribute to the Ocean. The orchestra’s rendition of Debussy’s “La Mer” and Ravel’s “Une Barque sur l’Océan” filled the hall with the sea’s mystery and power. Multimedia projections of marine life danced across the stage, reminding us that the ocean’s story is not just told in data and policy, but also in art, music, and emotion.

Highlights of the evening include eloquent statements from the Princess Lātūfuipeka of Tonga and a surprise appearance by Dr. Sylvia Earle. Both had stood on stage and spoke with the conviction of people who have dedicated their lives to learning from and sharing stories of the ocean. Princess Lātūfuipeka spoke to the sacredness of the ocean and its call to us. The ocean draws billions, and this call is beyond natural; it is a spiritual pull to connect with, listen to, and learn from the waters around us. Dr. Earle stated: “To protect the ocean is to protect ourselves.” Calls to action—delivered in the midst of music and art—reminded us that science and culture together can inspire change in ways that each discipline alone cannot.

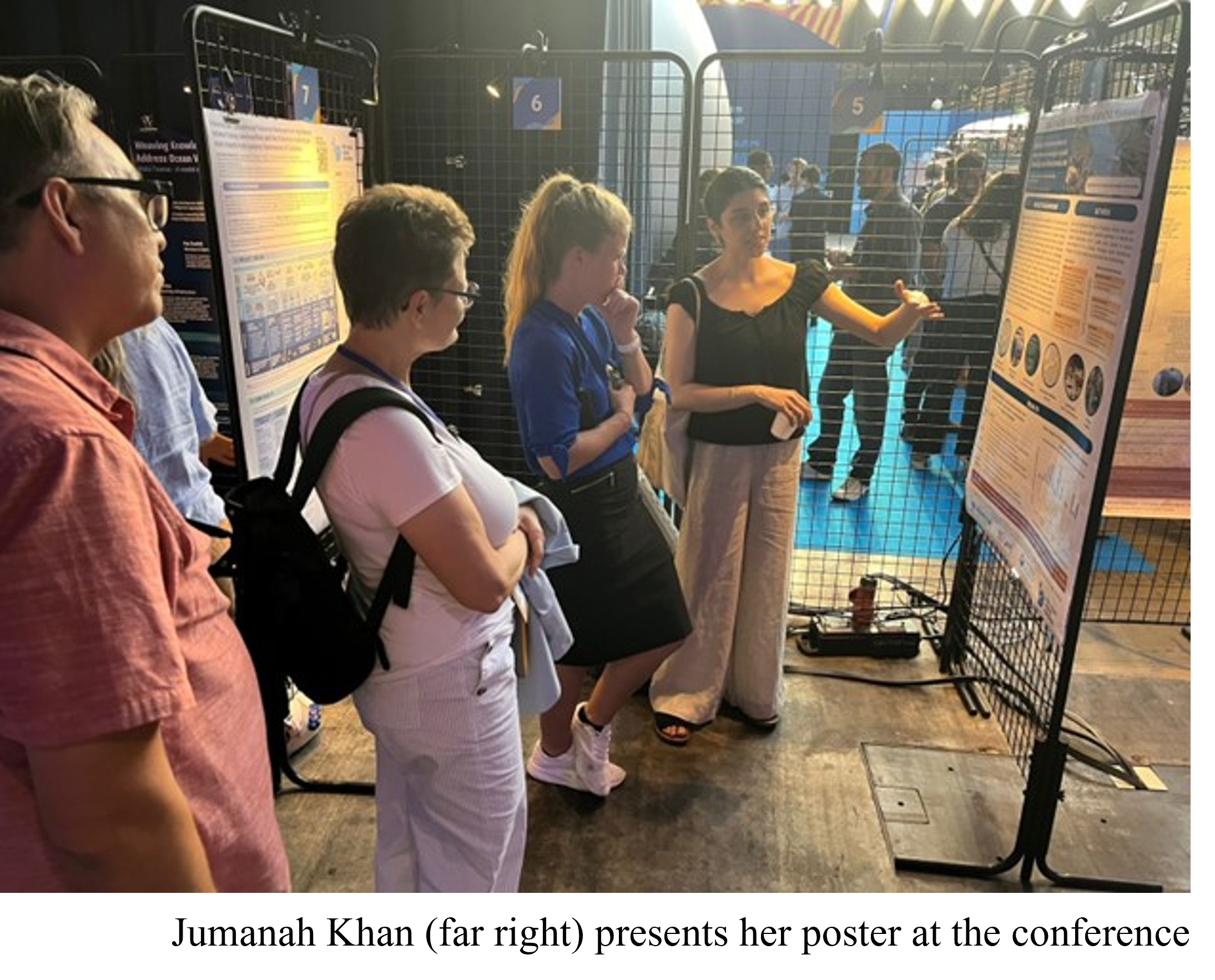

Presenting My Poster

Presenting my research at the OOSC was both humbling and energizing. The feedback I received reinforced the value of my work and the importance of inclusive, transparent communication in coastal spatial planning. By evaluating tools and their capacity to account for and communicate place-based knowledge, my research aims to improve the understanding and integration of the ways of knowing of those living and working in coastal environments. This integration is not just a matter of inclusion but is essential for trusted and context-specific decision-making.

As I heard echoed at OOSC: “We protect what we love, and we love what we know, but to know something, we have to understand.” This concept resonates with my research and the broader movement to make spatial planning more effective.

Looking Forward: From Congress to Action

As I left Nice, I carried a renewed sense of responsibility. The challenges are immense, but so is the collective will to meet them. As we move forward, we must embrace knowledge-based, inclusive, and adaptive approaches—balancing innovation with respect for both economic growth and Earth. In the words of a closing speaker: “Unity in the ocean, unity via the ocean.” We have one world, one ocean. Our future depends on what we choose to do, together, now.

Author: Jumanah Khan

Credits: All photographs by J. Khan

Tags: Marine & Ocean Issues; Public Policy & Decision-Making; Science-Policy Interface; Science Communication