Nova Scotia is defined by extensive, beautiful coastlines, where approximately 70% of the population lives within 20 kilometres of the shore (Government of Nova Scotia, n.d.a; NSECC, 2018). These coasts are vital to the province’s economy, providing essential ecosystem services, and contributing profoundly to the identity, pride, and way of life of Nova Scotians. However, the proximity to the coast exposes Nova Scotians to unrelenting coastal erosion, flooding, sea level rise, and storm activity driven by climate change, which constitute serious threats to coastal infrastructure, communities, and ecosystems (CLIMAtlantic, n.d.).

The Coastal Protection Act

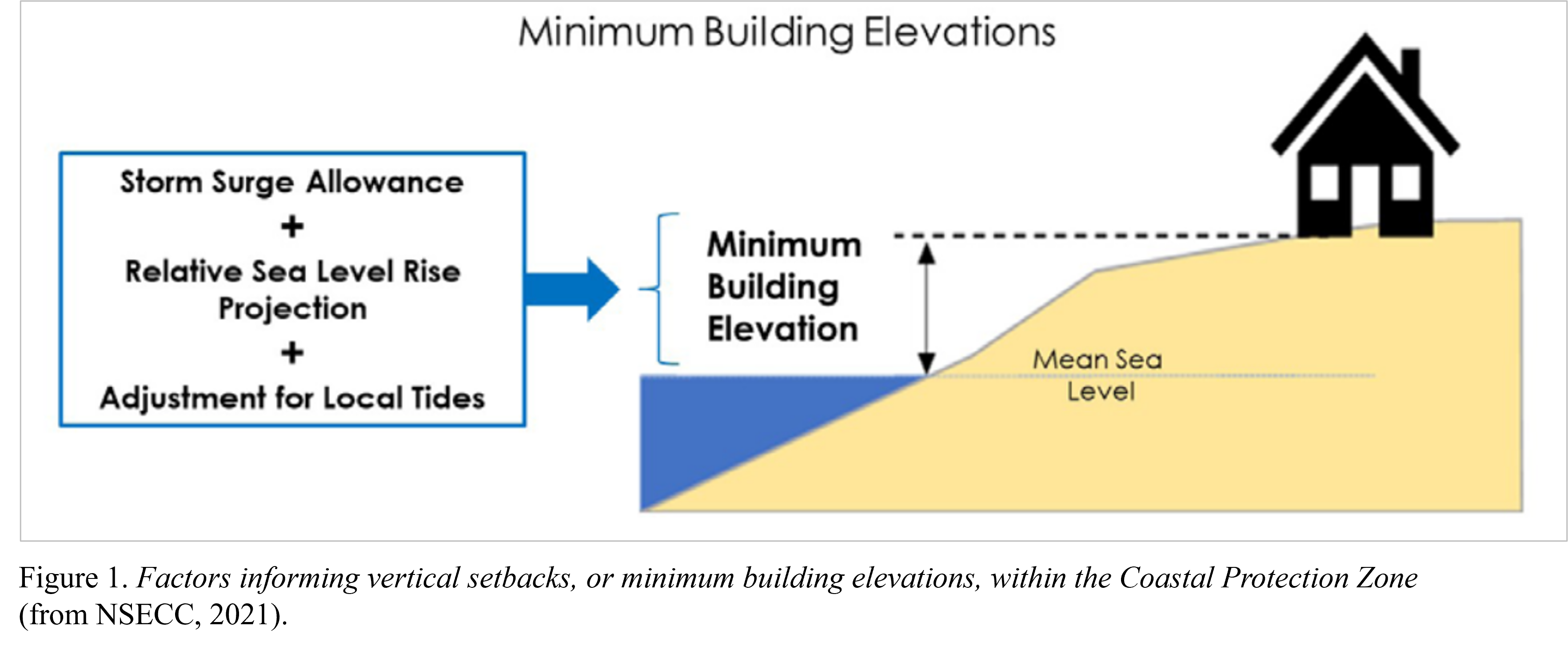

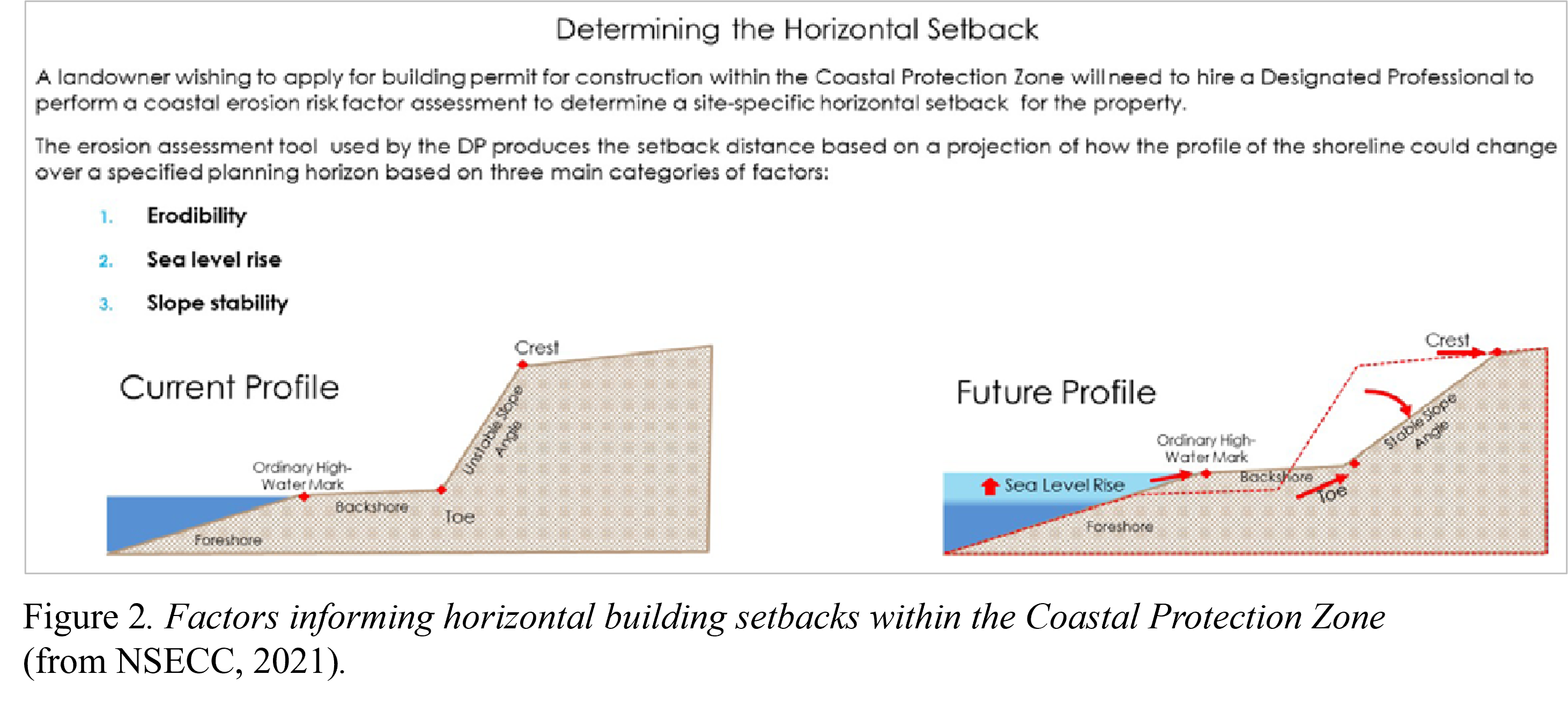

After extensive consultation, the provincial government responded to these ongoing threats by introducing the Coastal Protection Act, which was passed with all-party support in the Nova Scotia Legislative Assembly on 11 April 2019 (NSECC, 2019). The Act included a provision stating it would only come into force once the accompanying regulations were approved (The Dirt Gang, n.d.; Nova Scotia Legislature, n.d.). Developed over several years, the regulations proposed an 80-year planning horizon and outlined a Coastal Protection Zone, a narrow band along the province’s coasts where the regulations would apply. The regulations would have required that new construction within this zone comply with vertical and horizontal setbacks intended to protect structures from coastal flooding and erosion (NSECC, 2021) (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

When the Progressive Conservative Party was first elected to government in 2021, the Party promised to complete the regulations and proclaim the Act by 2023. In 2023, a delay until 2025 was announced, and in February 2024 the government decided it would not proclaim the Act at all (EAC, n.d.). This decision sparked unsurprising province-wide outrage, considering that all the consultations preceding the legislation had indicated public support for the Act. Public feedback from the 2021 consultation period, for example, emphasized the importance of environmental protection and timely, consistent implementation of the regulations (NSECC, 2022). Similarly, a survey sent to 40,000 coastal property owners in 2023 returned 1072 responses that, overall, supported the new coastal protection legislation (Group ATN Consulting, 2024).

Tim Halman, provincial Minister of Environment and Climate Change, used the same survey to justify the government’s decision to scrap the Coastal Protection Act. He claimed the roughly 39,000 non-responses indicated opposition to the Act. However, his claim does not accord with best-survey practices, as non-responses are not interpreted as dissent. Furthermore, since 1072 responses are sufficient for competent understanding of the survey questions, dismissing the survey was based on faulty reasoning (CBC News Nova Scotia, 2024; Gorman, 2024; K. Sherren, personal communication, 18 February 2025). Nevertheless, the provincial government chose to abandon this pioneering legislation. Instead, it replaced the Act with a Coastal Action Plan, entitled The future of Nova Scotia’s coastline: A plan to protect people, homes and nature from climate change (Province of Nova Scotia, 2024).

Present Challenges

Unlike the Act, the Action Plan relies entirely on the municipalities to take responsibility for coastal protection without providing clearly articulated guidelines. Nova Scotia’s municipalities vary widely in their capacity to address coastal development issues due to unequal resources, funding, and expertise for developing and enforcing protection plans (The Staff, 2024). To illustrate, the Halifax Regional Municipality’s budget at $1.3 billion, the largest municipal budget in the province (Halifax Regional Municipality, 2025), contrasts with approximately $27.3 million in Annapolis County. The latter is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change along its coasts as well as pressures from coastal development (Annapolis County, 2025; Bottomley, 2022). From a purely monetary perspective, Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) has substantially more financial resources for coastal management than the municipality of Annapolis, despite HRM’s population being only about 3.71 times larger. Unable, by law, to run deficits, municipalities often rely on federal funding to pursue large-scale projects, or they require provincial approval for long-term budgeting horizons (M. Donovan, personal communication, 7 March 2025; Tolley & Young, 2001). If provincial priorities change, municipalities are restricted in their ability to navigate between existing financial obligations and are often forced to operate with reduced funds (Tolley & Young, 2001).

In April 2025, the provincial government released new support tools about coastal planning and protection for the municipalities to use, including examples of bylaws, and about a $1.3 million funding allocation for the Nova Scotia Federation of Municipalities to hire a climate change policy analyst (Doucette, 2025). Although these developments are a positive step, coastal protection requires provincial leadership to achieve uniformly effective protection among Nova Scotia’s 49 municipalities.

Issues with the Scientific Framework

While the Action Plan outlines various scientific tools for coastal management, its description of the methods and data sources is unclear. In particular, the province-wide erosion risk assessment and Nova Scotia’s Municipal Flood Line Mapping Program lack scientific clarity and public accessibility (Province of Nova Scotia, 2024). Furthermore, no standardized or clear methods for performing erosion risk assessments are outlined in the plan.

Rather than providing specific objectives, the plan also outlines various steps in an unclear and non-sequential manner without the use of measurable targets or monitoring mechanisms. Despite its proclaimed three-year agenda, it is unclear whether further action will be pursued beyond 2027. Thus, the Action Plan needs to incorporate adaptive management strategies, which have become especially crucial for addressing the uncertainty and complexity of ever-changing coastal ecosystems. Without such strategies, the plan lacks an ecosystem focus, making it difficult to manage sensitive and fluctuating coastal habitats.

Lack of Legal Protection

In addition, the new plan lacks the legal authority necessary to ensure compliance, which contrasts with the enforceable provisions of the Coastal Protection Act. The Act would have set the legal foundation for making coastal risk assessments a necessary step in coastal development, while the Action Plan merely encourages the use of these assessments to inform individual decisions. The absence of enforceable regulations means legal consequences for non-compliance are absent, making it a legally insufficient approach to coastal protection.

Future Challenges

Looking ahead, it is critical to consider future challenges that may arise in the absence of a province-wide coastal management framework, such as (1) worsening coastal conditions, (2) increased litigation in the form of torts between neighbours or governmental negligence, and (3) heightened disaster relief funding.

In Nova Scotia, extreme weather events are becoming more intense and frequent (Government of Nova Scotia, n.d.b). In addition to one-time events, rising sea levels are a major climate risk, leading to a projected increase of up to one metre in relative sea level along the province’s coastlines by 2100 (Government of Nova Scotia, n.d.b; Lindsey, 2023; Savard et al., 2016). Nova Scotia has also been experiencing glacial isostatic adjustment since the last ice age. Thus, the province is experiencing two compounding effects: land sinking and sea rising, which are accelerating the time when Nova Scotia will see increased flooding of houses (Halifax Regional Municipality, n.d.).

The lack of a provincial framework can also lead to an overreliance on disaster relief, the cost of which will vastly outweigh expenditures for proactive protection measures. Rebuilding infrastructure, compensating homeowners, and repairing ecosystems can result in billions of dollars in expenses over time. As disasters become more frequent and severe, insurance premiums will rise, making coverage less available. Wealthier homeowners may be able to afford the escalating rate, but low and middle-income families will be left more vulnerable, making coastal development increasingly inaccessible to most.

Recommendation: The Coastal Adaptation and Stewardship Program

More than 85% of coastal lands in Nova Scotia are privately owned, highlighting the need to engage landowners in coastal management strategies (NSNT, 2025). Three types of public programming can influence resource conservation on private landholdings: 1) regulatory programs use legally mandated rules like the Coastal Protection Act, 2) market-based programs offer financial incentives through mechanisms like payments for ecosystem services, and 3) voluntary-based programs use non-mandatory mechanisms like the Action Plan (Kauneckis & York, 2009; Niemiec et al., 2019; Nuñez Godoy & Pienaar, 2023; Sweikert & Gigliotti, 2019).

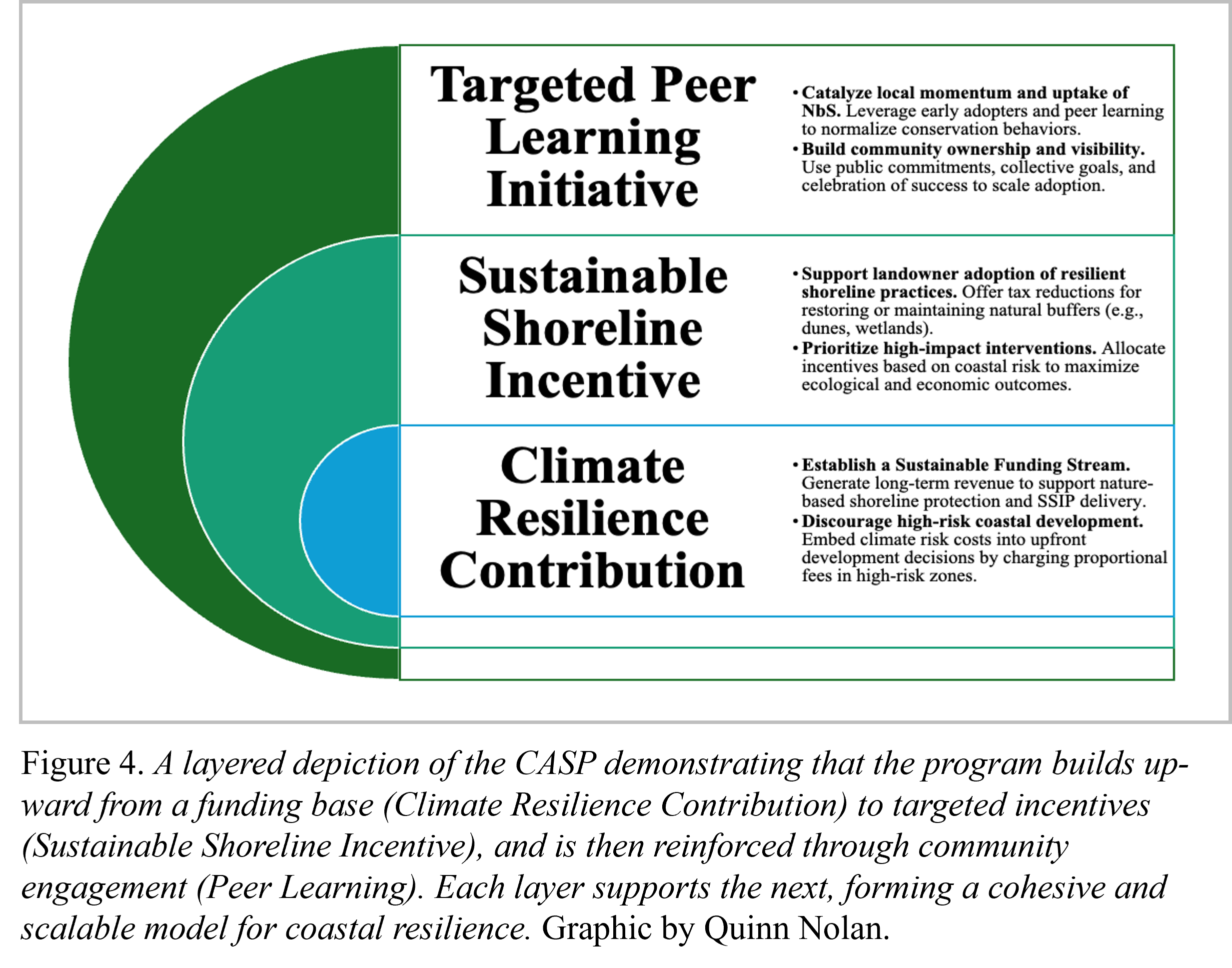

A hybrid approach integrating voluntary, regulatory, and market-based programs is most suitable for coastal protection in Nova Scotia’s current political climate. Thus, we propose a new framework dubbed the Coastal Adaptation and Stewardship Program (CASP), which includes three components: (1) a funding mechanism, (2) an incentive, and (3) community-level social interventions.

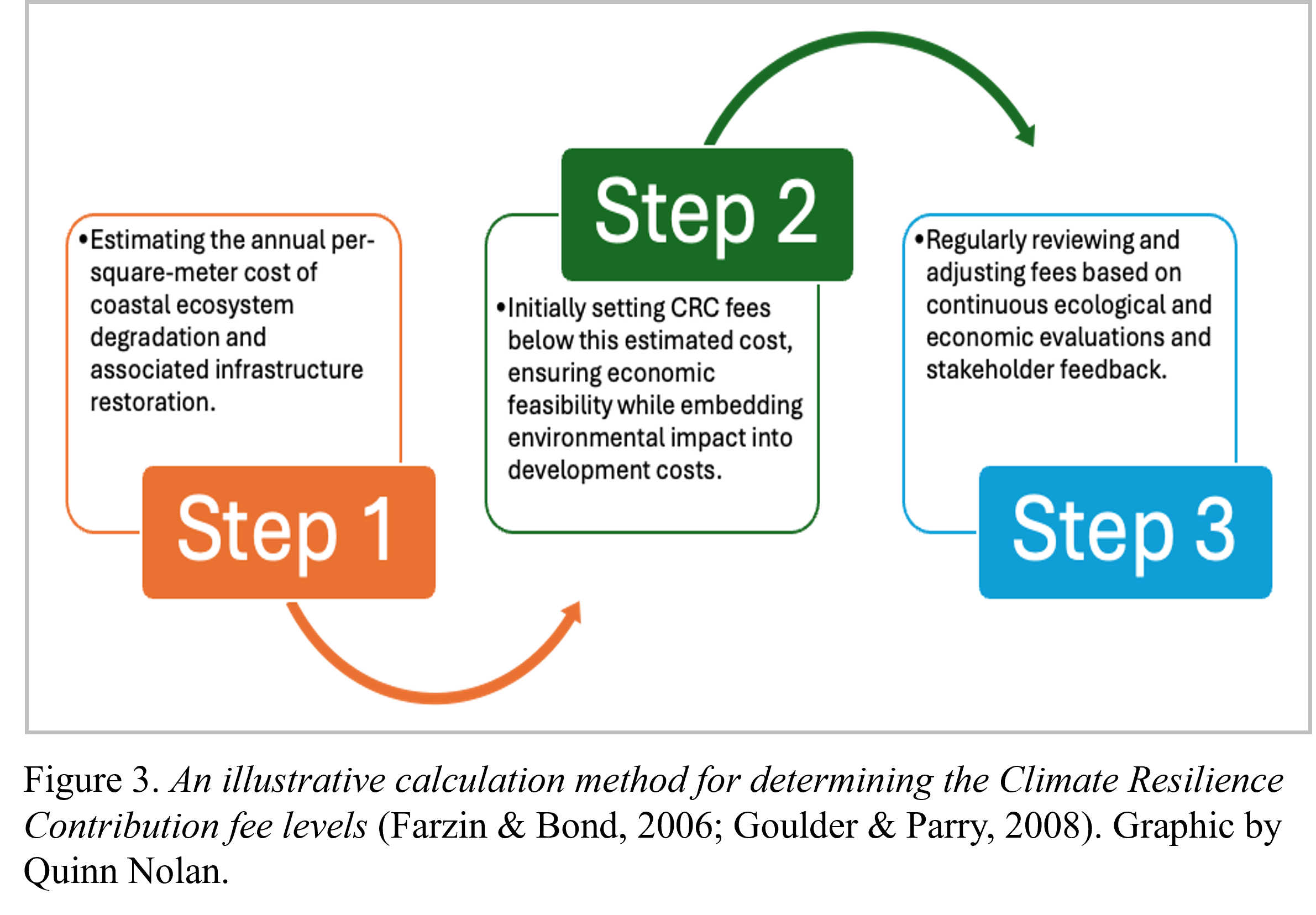

The Climate Resilience Contribution is a financial mechanism that aims to discourage development in ecologically sensitive and high-risk coastal areas by embedding the projected long-term costs of doing so into initial development expenses (see Figure 3). Additionally, it funds the Sustainable Shoreline Incentive Program, which will be used to incentivize coastal conservation and resilience efforts by offering property tax reductions to landowners who undertake conservation and restoration activities. This strategy aligns with evidence suggesting that financial incentives effectively influence landowner behaviour (Mitani & Lindhjem, 2022; Nuñez Godoy & Pienaar, 2023).

The final component of CASP emphasizes building broader community momentum through targeted peer learning initiatives. Recognizing that social dynamics play a pivotal role in the uptake of nature-based solutions, this proposed initiative engages early adopters—landowners and communities already open to ecological resilience practices—and amplifies their efforts through interventions such as neighbour discussion circles and collective goal-setting (McKenzie-Mohr & Schultz, 2014; Niemiec et al., 2019). In all, CASP offers a strategically layered approach to coastal protection in Nova Scotia and addresses both the political challenges and implementation gaps that stalled the Coastal Protection Act (see Figure 4).

While the Coastal Protection Act remains the most effective option for managing coastal development in the province, the current political climate makes its reinstatement unlikely. In this light, CASP presents a realistic alternative. Nova Scotia’s coastlines are too valuable to be left without protection. These recommendations reflect the urgent need for politically feasible, scientifically valid, and socially accepted solutions to ensure resilient, responsible coastal protection for future generations.

References

Annapolis County. (2025, March 18). 25-26 Approved operating budget. https://www.annapoliscounty.ca/images/2025/Finance/25-26_Approved_Operating_Budget_-_March_18_2025.pdf

Bottomley, J. (2022, March 19). Final draft: Flood risk assessment Town of Annapolis Royal. Town of Annapolis Royal. https://annapolisroyal.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/FRA-Town-of-Annapolis-Royal.pdf

CBC News Nova Scotia. (2024, March 19). Coastlines need protection. Is enough being done? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AvnTzYMqv-Y

CLIMAtlantic. (n.d.). Climate change impacts. https://climatlantic.ca/impacts/

The Dirt Gang. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions. https://thedirtgang.ca/coastal-coalition-nova-scotia/coastal-coalition-faq/

Doucette, K. (2025, April 15). Nova Scotia moves forward with plan for municipalities to protect

coastlines. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/ns-moves-forward-with-plan-to-force-municipalities-to-protect-coastlines-1.7510695

Ecology Action Centre [EAC]. (n.d.). Coastal Protection Act. https://ecologyaction.ca/our-work/coastal-water/coastal-protection-act

Farzin, Y. H., & Bond, C. A. (2006). Democracy and environmental quality. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 213-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.04.003

Gorman, M. (2024, March 7). N.S. environment minister says silence on Coastal Protection Act survey speaks volumes. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/coastal-protection-act-tim-halman-claudia-chender-zach-churchill-1.7136115

Goulder, L. H., & Parry, I. W. H. (2008). Instrument choice in environmental policy. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2), 152-174. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/ren005

Government of Nova Scotia. (n.d.a). Coastal climate change. https://novascotia.ca/coastal-climate-change/

Government of Nova Scotia. (n.d.b). Our changing climate. https://climatechange.novascotia.ca/changing-climate

Group ATN Consulting Inc. (2024). Nova Scotia coastal property owners consultation results. Government of Nova Scotia. https://0-nsleg–edeposit-gov-ns-ca.legcat.gov.ns.ca/deposit/b10744988.pdf

Halifax Regional Municipality. (n.d.). What causes flooding. Environment and Climate Change. https://www.halifax.ca/about-halifax/environment-climate-change/resilient-halifax-flooding/what-flooding/what-causes

Halifax Regional Municipality. (2025). Budget and business plan 2025/26. https://www.halifax.ca/sites/default/files/documents/city-hall/budget-finances/final-2025-26-budget-business-plan.pdf

Kauneckis, D., & York, A. M. (2009). An empirical evaluation of private landowner participation in voluntary forest conservation programs. Environmental Management, 44(3), 468-484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-009-9327-3

Lindsey, R. (2023). Climate change: Global sea level. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level

McKenzie-Mohr, D., & Schultz, P. W. (2014). Choosing effective behavior change tools. Social Marketing Quarterly, 20(1), 35-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500413519257

Mitani, Y., & Lindhjem, H. (2022). Meta-analysis of landowner participation in voluntary incentive programs for provision of forest ecosystem services. Conservation Biology, 36(1), e13729. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13729

Niemiec, R. M., Willer, R., Ardoin, N. M., & Brewer, F. K. (2019). Motivating landowners to recruit neighbors for private land conservation. Conservation Biology, 33(4), 930-941. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13294

Nova Scotia Environment and Climate Change [NSECC]. (2018). Developing coastal protection legislation. Government of Nova Scotia. https://cdn.halifax.ca/sites/default/files/documents/city-hall/boards-committees-commissions/180801sprwab531.pdf

Nova Scotia Environment and Climate Change [NSECC]. (2019). New coastal protection legislation. Government of Nova Scotia. https://news.novascotia.ca/en/2019/03/12/new-coastal-protection-legislation#:~:text=Today%2C%20March%2012%2C%20Environment%20Minister%20Margaret%20Miller,greater%20risk%20of%20flooding%20and%20coastal%20erosion

Nova Scotia Environment and Climate Change [NSECC]. (2021). Part 2: A detailed guide to proposed Coastal Protection Act regulations. Government of Nova Scotia. https://web.archive.org/web/20220408045550/https://novascotia.ca/coast/docs/part-2-detailed-guide-to-proposed-Coastal-Protection-Act-Regulations.pdf

Nova Scotia Environment and Climate Change [NSECC]. (2022). Consultation on the proposed Coastal Protection Act regulations: What we heard. Report of public input received during the summer 2021 consultation period. Government of Nova Scotia. https://thedirtgang.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Coastal_Protection_Act_-_Public_Engagement_Report.pdf

Nova Scotia Legislature. (n.d.). How a bill becomes law. https://nslegislature.ca/about/how-legislature-works/how-bills-become-law#:~:text=After%20approval%20on%20third%20reading,referred%20to%20as%20an%20Act

Nova Scotia Nature Trust [NSNT]. (2025). About the Nature Trust: History. https://nsnt.ca/about/history/#:~:text=Over%2070%25%20of%20land%20is,including%2085%25%20of%20the%20coastline

Nuñez Godoy, C. C., & Pienaar, E. F. (2023). Motivations for, and barriers to, landowner participation in Argentina’s payments for ecosystem services program. Conservation Science and Practice, 5(8), e12991. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12991

Province of Nova Scotia. (2024). The future of Nova Scotia’s coastline: A plan to protect people, homes, and nature from climate change. Nova Scotia, Canada. https://novascotia.ca/coastal-climate-change

Savard, J.-P., van Proosdij, D. & O’Carroll, S. (2016). Chapter 4: Perspectives on Canada’s east coast region. In D. S. Lemmen, F. J. Warren, T. S. James & C. S. L. Mercer Clarke (Eds.), Canada’s marine coasts in a changing climate (pp. 99-152). Ottawa: Government of Canada. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/earthsciences/pdf/assess/2016/Coastal_Assessment_Chapter4_EastCoastRegion.pdf

The Staff. (2024, June 19). Nova Scotia’s Lunenburg Municipality passes coastal protection regulations. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/10576047/lunenburg-coastal-protection-regulations/

Sweikert, L. A., & Gigliotti, L. M. (2019). Evaluating the role of Farm Bill conservation program participation in conserving America’s grasslands. Land Use Policy, 81, 392-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.023

Tolley, E. & Young, W. R. (2001). Municipalities, the constitution, and the Canadian federal system. Government of Canada Publications. https://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/bp276-e.htm

Authors: Aidan Buhler, Monique Guevara, Brynne Thompson, and Quinn Nolan

This post is based on a research project completed by the authors in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Biophysical Dimensions of Resource and Environmental Management (ENVI 5505), Socio-political Dimensions of Resource and Environmental Management (ENVI 5500), and Law and Policy for Resource and Environmental Management (ENVI 5205) offered in the Master of Resource and Environmental Management program by the School for Resource and Environmental Studies at Dalhousie University.

Image credits: The photograph of the Nova Scotia coastal scene was taken by P. G. Wells in September-October 2011. Figures 1 and 2 were reproduced from Nova Scotia Environment and Climate Change, 2021. Figures 3 and 4 were created by Quinn Nolan

Tags: Marine & Ocean Issus; Public Policy and Decision Making; Student Submission