Science education is an integral part of the curriculum of many schools, yet how science actually works and how new knowledge is produced is rarely covered in their courses. School books and experiments with a pre-determined outcome and defined solution do not reflect the actual work of researchers, which involves trial and error, dealing with uncertainties and finding creative solutions to novel problems. Citizen science projects could offer a more realistic image about research. These scientific studies aim to involve the public in several research processes, for example, the formulation of research questions, the development of scientific methods, or data collection. As an aside, some scholars debate whether the label “citizen science” is appropriate as not all participants may be or identify as citizens of a respective country (see Eitzel et al., 2017 for a critical discussion about this terminology).

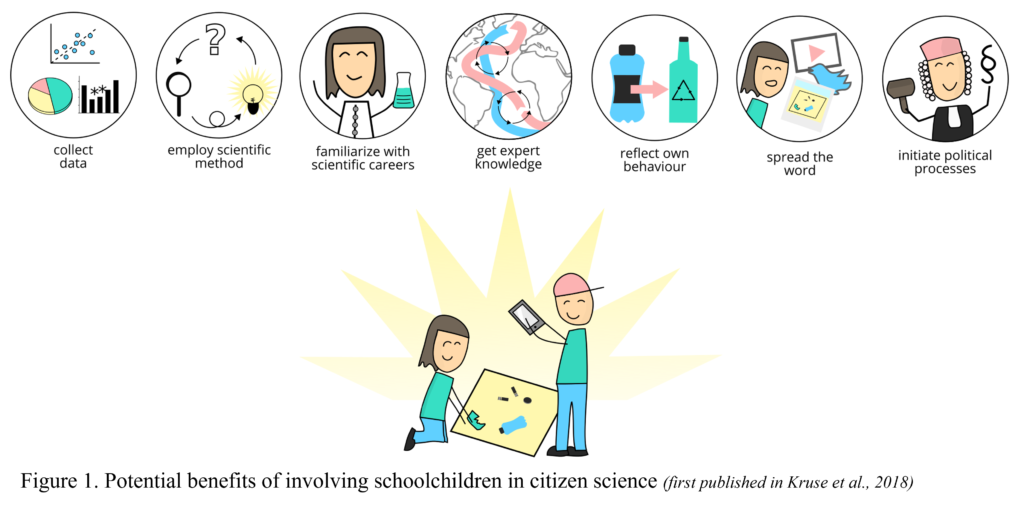

Besides the scientific practices noted above, citizen science projects involving schoolchildren commonly are guided by educational goals, such as improving the scientific and data literacy of participants or transmitting expert knowledge about a particular subject. I am involved with the Plastic Pirates project, which seeks to improve schoolchildren’s understanding of the societal interactions between our consumerist lifestyle and environmental impacts of plastic pollution. We endeavour to empower schoolchildren who temporarily identify as researchers (see Figure 1) as they establish sampling areas, collect litter and plastic samples, and classify, annotate, and analyse their findings of local litter pollution at a river, lake, or ocean sampling site (see this video for the sampling method). Plastic Pirates was founded by the Kiel Science Factory, the School lab of Kiel University, Germany, and the Científicos de la Basura citizen science network in Chile. Since the launch of Plastic Pirates more than 25,000 schoolchildren from over 1,700 German schools have been involved and the project has since expanded to 12 other European countries. A pilot phase of the Plastic Pirates was conducted in Canada with approximately 220 school children and their teachers from seven schools in Nova Scotia in the fall of 2024 (see the initial results in this report).

Ultimately, aside from the educational goals mentioned above, analysing the data collected by the schoolchildren and publishing the results in international, peer-reviewed scientific journals, as any scientist would, is a primary objective. During the peer-review process usually someone raises the question about whether schoolchildren can reliably employ research methods and collect acceptable scientific data and information. Schoolchildren have not yet finished their formal education; how could they conduct research? The feedback of one reviewer of our first Plastic Pirates study illustrates this concern:

I appreciated [the] authors’ great effort to collect on a large-scale basis data on plastic litter in riverine ecosystems. I also appreciate very much the scientific approach applied by the authors … into a not scientific context such as Citizen Science is….[but] I’m also persuaded that, not all citizen science experiences have the same scientific rigor and less rigorous activities should not have (in my opinion) the chance to present collected data for the publication [in] a scientific journal of high impact. (anonymous reviewer of Kiessling et al., 2019)

Reviewers of research manuscripts should be critical as scrutiny of methodologies and research approaches is expected. Unfortunately, though, this reviewer categorically disqualified citizen science studies as unscientific and argued that the results should be presented as outreach and citizen engagement rather than in journals where the research community publishes and shares knowledge.

Following the referee’s review, we systematically implemented and formalized several approaches to demonstrate that the methods employed in the Plastic Pirates project are, in fact, robust. We even published a short paper about data quality in this citizen science project (Dittmann, et al., 2022). Eventually, we published several papers, contributing substantially to our understanding of the plastic pollution problem in rivers in Germany. For example, we are now aware about litter quantities (~0.8 items /m2) which did not substantially increase or decrease over the past seven years (Dittmann, et al., 2024), that a sizeable volume of litter consists of problematic single-use plastics (Kiessling, et al., 2023), and that some small rivers are heavily polluted by microplastics (Kiessling, et al., 2021).

Without the involvement of schoolchildren and their enthusiastic teachers, we would not have been able to obtain this knowledge. They were a vital part of this initiative! In fact, my doctoral degree was based on analysing and interpreting the research data the schoolchildren collected. So, for me, the answer to the first question, “Can schoolchildren contribute to research?” is a resounding Yes!

A provocative follow-up question is: “Do the schoolchildren actually care about the science and research articles?” While the value of the research contribution of the schoolchildren is obvious to my colleagues and me, the research is often presented in a format that remains out of grasp for the schoolchildren and likely many teachers as well. A double-column article published in English in a research journal the schoolchildren have never heard about remains hardly understandable to them (and their teachers). Even though we undertook some efforts to make the research more accessible to them (e.g., YouTube videos in German), explaining how their research contribution could lead to real-world changes would be more empowering in my opinion.

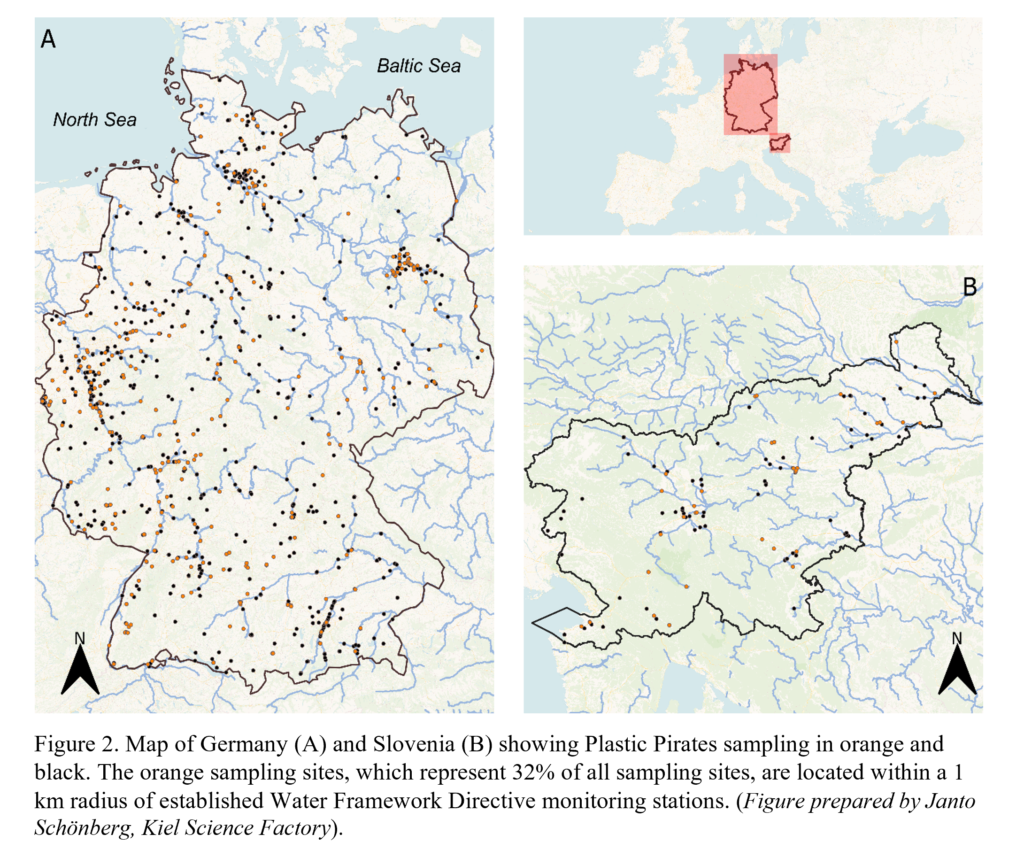

Which raises the second question: “Can schoolchildren, through citizen science, be involved in policy-making?” or “How do we make the research of the schoolchildren count?” Spoiler alert: there is no definitive answer yet. Currently, our team is discussing how to add additional value to the research data collected by the schoolchildren. Specifically, we evaluated the potential that the data could contribute to the Water Framework Directive of the European Union. This policy aims to obtain “a good status” of rivers, lakes, and coastal waters in the European Union. Interestingly, so far, the Directive is not concerned with litter and thus not with plastic pollution. We, therefore, suggest that the data collected by the Plastic Pirates, alongside data collected by other citizen science initiatives (such as the International Coastal Cleanup or Marine Litter Watch could present baseline data for the Water Framework Directive. Further, we imagine that in the future school-based citizen science projects could collaborate with authorities implementing this directive. For example, the data could fill gaps and harness the local knowledge and environmental concern of the children and their teachers. Our data from Germany and also Slovenia show that a substantial number of the Plastic Pirates sampling sites are in close proximity to the vast network of sampling stations related to the Water Framework Directive (see Figure 2).

What are the next steps? We need to initiate an open dialogue between stakeholder groups, meaning schoolchildren, teachers, and researchers associated with citizen science initiatives on the one hand, and policy makers and Water Framework Directive managers on the other. A long and pain-staking process may be necessary, as boundary work undertaken in Ghana regarding the usability of citizen science-generated plastic pollution data for policymaking showed (Fraisl, et al., 2023). The benefits though could be substantial. I believe that value and credibility is added to research studies and policy-making processes by broader societal involvement. This boundary dialogue could achieve much-needed trust in policymaking institutions, which are often inaccessible and not transparent to many citizens. For young people and schoolchildren, especially, this initiative would be a rare opportunity to actually participate, be involved, and potentially feel empowered.

References

Dittmann, S., Kiessling, T., Kruse, K., Brennecke, D., Knickmeier, K., Parchmann, I., & Thiel, M. (2022). How to get citizen science data accepted by the scientific community? Insights from the Plastic Pirates project. Proceedings of Engaging Citizen Science Conference 2022 — PoS(CitSci2022), 124. https://doi.org/10.22323/1.418.0124

Dittmann, S., Kiessling, T., Knickmeier, K., Schönberg, J., Brennecke, D., Hinzmann, M., Knoblauch, D., & Thiel, M. (2024). Temporal variability of litter pollution of rivers in Germany – A long-term assessment by schoolchildren as citizen scientists. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 209, 117253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117253

Eitzel, M. V., Cappadonna, J. L., Santos-Lang, C., Duerr, R. E., Virapongse, A., West, S. E., Kyba, C. C. M., Bowser, A., Cooper, C. B., Sforzi, A., Metcalfe, A. N., Harris, E. S., Thiel, M., Haklay, M., Ponciano, L., Roche, J., Ceccaroni, L., Shilling, F. M., Dörler, D., … Jiang, Q. (2017). Citizen science terminology matters: Exploring key terms. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.96

Fraisl, D., Topouzelis, K., Seidu, O., See, L. & Rabiee, M. (2023). Feasibility study on marine litter detection and reporting in Ghana. New York: Thematic Research Network on Data and Statistics (TReNDS). https://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/19134/1/Feasibility%2BReport%2Bv6.pdf

Kiessling, T., Knickmeier, K., Kruse, K., Brennecke, D., Nauendorf, A., & Thiel, M. (2019). Plastic Pirates sample litter at rivers in Germany – Riverside litter and litter sources estimated by schoolchildren. Environmental Pollution, 245, 545-557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.11.025

Kiessling, T., Knickmeier, K., Kruse, K., Gatta-Rosemary, M., Nauendorf, A., Brennecke, D., Thiel, L., Wichels, A., Parchmann, I., Körtzinger, A., & Thiel, M. (2021). Schoolchildren discover hotspots of floating plastic litter in rivers using a large-scale collaborative approach. Science of The Total Environment, 789, 147849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147849

Kiessling, T., Hinzmann, M., Mederake, L., Dittmann, S., Brennecke, D., Böhm-Beck, M., Knickmeier, K., & Thiel, M. (2023). What potential does the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive have for reducing plastic pollution at coastlines and riversides? An evaluation based on citizen science data. Waste Management, 164, 106-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2023.03.042

Kruse, K., Knickmeier, K., Kiessling, T., Brennecke, D., & Bratz, H. (2018) Plastikmüll im ozean: Eine untersuchung im fachraum und freiland. Naturwissenschaften im Unterricht – Chemie, 29(165), 23-26. https://oceanrep.geomar.de/id/eprint/48044

Author: Tim Kiessling

Tim Kiessling is a marine biologist researching the environmental problem of plastic pollution through citizen science and community science approaches. From August to November 2024 he was an Ocean Frontier Institute Visiting Post-Doctoral Fellow working with Dr. Tony R. Walker, School for Resource and Environmental Studies, Dalhousie University. While in Halifax, he presented a public lecture (slides; video) related to this blog post, which was co-sponsored by the Dalhousie Department of Information Science and EIUI).

Tags: Information Use & Influence; Public Policy & Decision-Making; Science-Policy Interface; Scientific Communication

Image credits: Title figure and Figure 1: Tim Kiessling. Figure 2: Janto Schönberg. All images use the Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.