In a time when humanity faces existential threats from climate change and ecosystem collapse, the need for transformative change has never been more urgent. Now, more than ever, academics need to move beyond their traditional role as knowledge generators to become knowledge brokers and public activists to facilitate stronger evidence-informed decision making (Gardner et al., 2021; Gluckman et al., 2021; Tormos-Aponte et al., 2023). We can look to scientists who have embraced these roles to better understand what actions and processes have allowed them to act as leaders in advocacy and political action. Alexandra Morton, a marine biologist and science advocate, exemplifies how scientists can engage in advocacy and activism to act as knowledge brokers for the public and decision-makers.

In a time when humanity faces existential threats from climate change and ecosystem collapse, the need for transformative change has never been more urgent. Now, more than ever, academics need to move beyond their traditional role as knowledge generators to become knowledge brokers and public activists to facilitate stronger evidence-informed decision making (Gardner et al., 2021; Gluckman et al., 2021; Tormos-Aponte et al., 2023). We can look to scientists who have embraced these roles to better understand what actions and processes have allowed them to act as leaders in advocacy and political action. Alexandra Morton, a marine biologist and science advocate, exemplifies how scientists can engage in advocacy and activism to act as knowledge brokers for the public and decision-makers.

In the late 1970s, Morton began to notice that wild salmon were dying near her home in the Broughton Archipelago of British Columbia. This observation led her to study the effects of salmon farming on wild salmon populations, and she concluded that wild salmon were experiencing parasite and disease outbreaks as a result of contact with open-pen fish farms (Morton, 2021). After publishing her results, she faced severe pushback from members of the aquaculture industry and government. Over the next several decades, she engaged with several groups to raise public awareness around the issue and convince decision-makers to stop the restocking of these open-pen farms (Morton, 2021). This blog post uses Morton’s advocacy work as a case study to explore the themes of knowledge brokerage, activism, advocacy, and the path from research to action.

Bridging and brokerage

Policymakers and knowledge makers (like scientists, researchers, and academics) have significantly different processes and values, leading to a divide between the two communities that makes communication a complex process (Gluckman et al., 2021). Boundary-spanning actors and organizations, known as brokers, help to bridge this divide between groups, increasing trust and transparency in government decision making processes (Gluckman et al., 2021).

Knowledge brokers, who can be thought of as bridge-builders, help to translate the different languages of the two communities (Gluckman et al., 2021; Tormos-Aponte et al., 2023). Brokers are not, however, passive translators. They help to “align information needs with outputs,” ensuring that decision-makers have framed their questions appropriately, and that they receive advice based on robust evidence (Gluckman et al., 2021). They take scientific information directly from researchers, synthesizing and presenting it to meet the specific needs of policy makers, and therefore paving the road for science to have an impact on decision making (Cadman et al., 2020; Gluckman et al., 2021). Brokerage is a type of boundary function, so brokers are in a position to put aside their own values and beliefs, instead ensuring that evidence is presented with clarity, and communicated in a way that acknowledges all of its dimensions (Gluckman et al., 2021). This honesty serves to increase both the legitimacy and credibility of scientific information within the decision-making process (Cadman et al., 2020).

An example of organizations engaging in brokerage are the environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) in the environmental and marine policy sphere following the first election of the Liberal Party under Justin Trudeau to national leadership in Canada in 2015. Two Canadian ENGOs, the Ecology Action Centre and the World Wildlife Fund Canada, were encouraged by the federal government to assist in their goal of protecting Canada’s territorial ocean. These organizations commonly engaged in what researchers referred to as “soft advocacy,” which involved searching for consensus and relationship building amongst stakeholders (Cadman et al., 2020). The ENGOs leveraged strategic information gathering and communication in this position with the federal government to communicate and achieve their targets.

Activism versus advocacy

Although academics can provide recommendations to policy makers by publishing their research, few engage with more direct pathways of influence, such as advocacy and activism. Advocacy can be considered to operate within “proper channels” of influence, and may involve lobbying, campaigning, and public outreach (Gardener et al., 2021). In contrast, activism uses more direct actions to influence policy, such as protest and non-violent civil disobedience (Gardener et al., 2021). Alexandra Morton relied heavily on activist actions to sway decision-makers and public opinion in the case of salmon farms. In one notable protest effort, she led a walk called the Get out Migration, when she walked ~300 km from her home in Echo Bay to the legislature in Victoria, British Columbia with a crowd that grew to over a 1000 concerned citizens to address the environmental impacts of open-pen salmon farms. Morton’s earnest engagement in activism set her apart from many of her peers in the scientific community and demonstrates the potential for academics to engage in effective activism.

As introduced above, two ENGOs assisted the federal government in achieving marine protection targets. This approach is an example of activists entering the “proper channels” of advocacy as defined by Gardener et al (2021). However, this transition was not without challenges. Notable tensions occurred as these ENGOs shifted from activism to advocacy. Normally politically independent and situated outside of government, they now assumed a more insider position. This step inhibited their ability to maintain a public image of non-state actors and threatened their perception of credibility as they influenced decision-making from the inside (Cadman et al., 2020). This case highlights the inherent tensions in institutional advocacy, where gaining influence within formal power structures can sometimes undermine a person or an organization’s perceived integrity.

Research to action

One of the most powerful tools scientists have in their toolkit is public engagement. Through engaging the public, as well as utilizing their networks and organizations, scientists can influence decision-makers and shape policy discussions (Tormos-Aponte et al., 2023). By making scientific issues understandable and relevant to everyday life, they can help mobilize public support.

Alexandra Morton’s work in promoting wild salmon conservation in British Columbia is a good example of how scientists can effectively engage in advocacy to drive policy change. She gained public support and interest by translating her scientific findings on the dangers of open-net fish farms into accessible language that is suitable for the media (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Examples of News Articles about Morton’s Work Designed for Public Readership

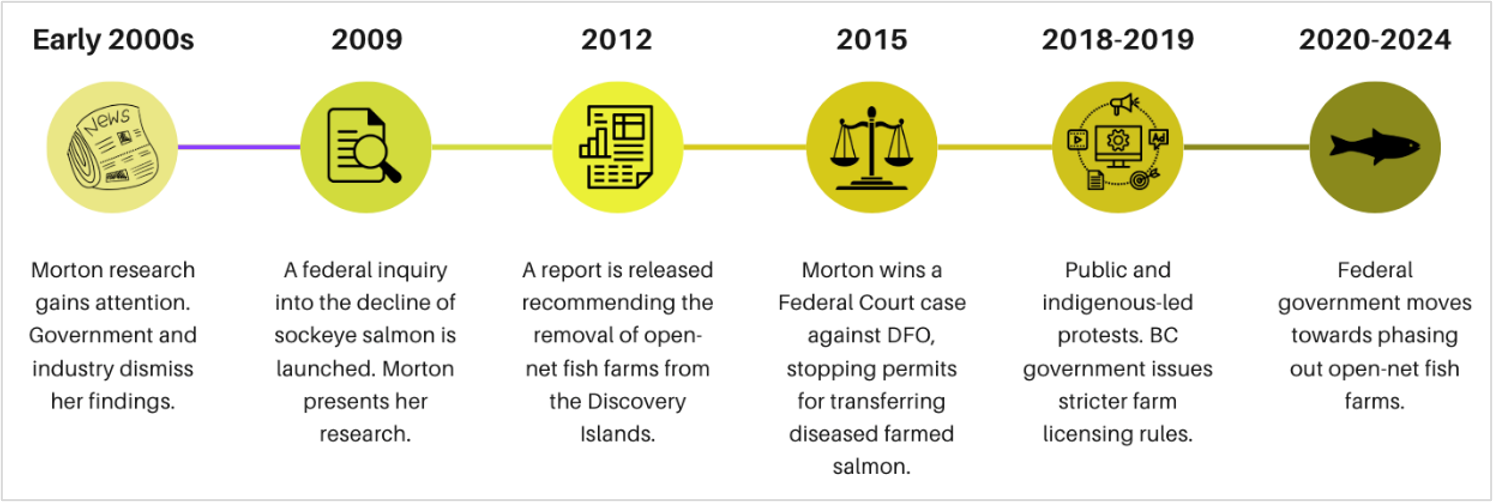

Morton also published a booklet called the Salmon Confidential, which simplified complex ecological concerns into a compelling narrative and was even featured in the documentary that reached two million people and helped garner support for the movement (Morton, 2021). By connecting with social movements and highlighting what was at stake, Morton was able to pressure policymakers to act (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Timeline of Public and Policy Responses to Morton’s Advocacy

Scientists can also directly influence decision-makers by framing scientific problems effectively and advocating for inclusive, evidence-based solutions (Tormos-Aponte et al, 2023). Morton did this by consistently presenting her research on how parasites and diseases from open-net fish farms were harming wild salmon. Rather than merely presenting data, she actively lobbied policymakers, participated in regulatory hearings, and used legal avenues to hold the government accountable (Morton, 2021). Her persistence in using science as a tool for advocacy demonstrates that when scientists or academics engage in activism, they have the power to influence significant change.

Final thoughts

The role of scientists and their respective organizations must extend beyond knowledge generation to undertake active participation in decision making. Alexandra Morton’s persistent efforts to protect the wild salmon of British Columbia provide a strong case for how scientists can become knowledge brokers to bridge the gap between research and policy through public engagement and direct – possibly disobedient – actions. Her work highlights the challenges and opportunities inherent to these roles, and evidence from current literature provides an opportunity to reflect on the differences between activism and advocacy, as well as the balance between public trust and credibility while aiming to influence decision making.

When scientists take an active role in the policy arena, whether through direct engagement with decision-makers or in grassroots mobilization, they have an opportunity to drive transformational change. In embracing their role as both knowledge brokers and public advocates, scientists can promote action about critical environmental issues, ensuring the issues receive the attention they deserve.

References

Cadman, R., MacDonald, B. H. & Soomai, S. S. (2020). Sharing victories: Characteristics of collaborative strategies of environmental non-governmental organizations in Canadian marine conservation. Marine Policy, 115, 103862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103862

Gardner, C. J., Thierry, A., Rowlandson, W., & Steinberger, J. K. (2021). From publications to public actions: The role of universities in facilitating academic advocacy and activism in the climate and ecological emergency. Frontiers in Sustainability, 2. Article 879019. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2021.679019

Gluckman, P. D., Bardsley, A., & Kaiser, M. (2021). Brokerage at the science-policy interface: From conceptual framework to practical guidance. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00756-3

Morton, A. (2021). Not on my watch: How a renegade whale biologist took on governments and industry to save wild salmon. Toronto: Random House Canada.

Tormos-Aponte, F., Brown, P., Dosemagen, S., Fisher, D. R., Frickel, S., MacKendrick, N., Meyer, D. S., & Parker, J. N. (2023). Pathways for diversifying and enhancing science advocacy. Science Advances, 9(20), eabq4899. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq4899

Authors: Emma Hak-Kovacs, Saarah Kunaseelan, Breagh MacDermid, and Amy Sutley

Image Credits: Figure 1: The snippets from news articles were obtained from: Bennett, N. (2023, September 14). Sea lice dropped after salmon farms removed: Study. BIV-Business in Vancouver. https://www.biv.com/news/environment/sea-lice-dropped-after-salmon-farms-removed-study-8273340 and Hasegawa, R. (2019, June 2). Sea louse found in packaged salmon from North Vancouver store. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/vancouver/article/sea-louse-found-in-packaged-salmon-from-north-vancouver-store/; Figure 2: Created by Saarah Kunaseelan with information from Morton, A. (2021). Not on my watch: How a renegade whale biologist took on governments and industry to save wild salmon. Toronto: Random House Canada.

This blog post is part of a series of posts authored by students in the graduate course “Information in Public Policy and Decision Making” offered at Dalhousie University.

Tags: Information Use & Influence; Public Policy & Decision Making; Science-Policy Interface; Scientific Communication; Student Submission